A few weeks ago, we met Sir William Mulock, originally of Bond Head. This week, we look at the greatest misstep of his political career, an engineering folly known today as the ghost canal.

The story of these ruins begins in 1904, when Mulock, then-minister of labour and public works in the Liberal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, began pressing for a canal to link his adopted hometown of Newmarket with the Trent-Severn Waterway. The proposed canal would follow the Holland River from Cooks Bay on Lake Simcoe south to Newmarket and, presumably, be a boon to local industry and tourism.

Politics, far more than practicality, dictated the development of the Newmarket Canal. Mulock had lured many industries to the community and knew his political fortunes rode in tandem with the prosperity of Newmarket’s economy. In the face of rising railway freight fees that threatened local industry, Mulock devised the canal concept because shipping by water was cheaper than rail.

He presented the idea in 1904, and the project was accepted even in the face of mounting evidence it would face daunting engineering obstacles. He rode a wave of popularity and was easily re-elected in the 1905 election. His plan had worked perfectly.

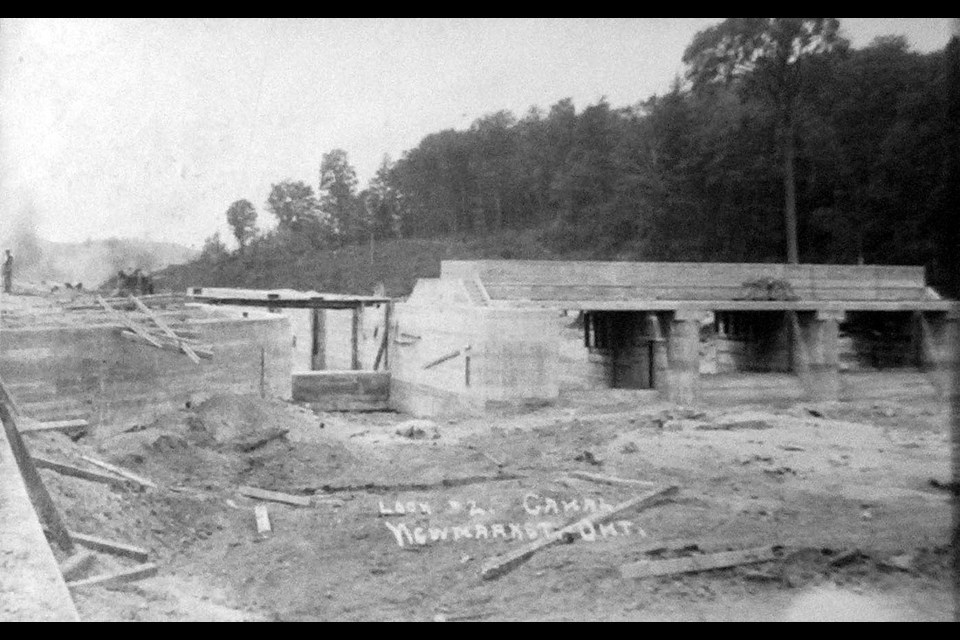

Construction of the canal was an engineering nightmare, largely because the Holland River is so shallow. To compensate, plans called for extensive dredging, the construction of storage tanks to collect water from spring floods and rainfall, and the installation of several locks and dams. In addition, retaining walls, pipe culverts, swing bridges and docks would have to be built.

Work was undertaken in two stages. The first, from Lake Simcoe to Holland Landing — 15 kilometres — was at lake level and required no locks. The second, from Holland Landing to Newmarket, would require three locks over seven kilometres because of a 14-metre rise in elevation.

Soon, many people began to have second thoughts about the canal. It seemed like a large and expensive project for the few passenger steamers or freight barges that could be expected to make use of it each season. And would it even work? There were serious doubts the Holland River would ever be able to accommodate ships with anything but the shallowest of drafts.

Still, construction continued. By 1911, about two-thirds of the canal was complete — including three lift locks, three swing bridges and a turning basin — but at astronomical cost.

The 1911 election saw Laurier defeated by Robert Borden. With the change of government, construction on the Newmarket Canal was abandoned.

Remnants can still be seen today. One lock structure can be seen in Holland Landing, where Old Yonge Street enters the village. Another lock and the remains of a swing bridge lie within Rogers Reservoir, off Green Lane.